by Emma Middleton, University of Edinburgh.

In 1852 Alexis, a patient of the Royal Edinburgh Asylum (REA) and regular contributor to the patient-produced REA magazine The Morningside Mirror, reminisced:

How changed is the treatment of the insane in my recollection! With that sedulous attention and gentleness, contrasted with the cruel, because ignorant, discipline of former days, are they cared for! Coercion and restraint have been superseded by mercy and regulated liberty. This is a good-natured age, will all its hubbub of pseudo-philanthropy and golden dreams and mad speculation.[1]

As Alexis suggested, in the nineteenth century there was a revolutionary transformation in the treatment of the insane. A key agent of this shift was ‘moral treatment’.

Historians and medical professionals alike have pronounced the emergence of moral treatment in Britain the great turning point in the treatment of the insane, marking the emergence of the modern psychiatric enterprise.[2] The point of departure in histories of moral treatment is often Phillipe Pinel’s 1806 text, Treatise on Insanity. Pinel condemned the insalubrious conditions of asylums and asserted that a positive environment should support the treatment of insanity. Mechanical restraint and repressive management were rejected, suggesting that inhumane treatment only exacerbated insanity. Instead, ‘consolatory language, kind treatment and the revival of extinguished hope’[3] were to constitute the asylum regime and lunatics were not to be considered as ‘completely devoid of reason’.[4] Vitally, inmates were to be allowed a degree of freedom and their minds were to be occupied using ‘moderate employment and regular exercise’.[5] These methods of treating the insane and organising the asylum constituted what Pinel termed ‘moral treatment’.

The REA was the largest and most prestigious asylum in nineteenth-century Scotland. As part of the REA moral treatment regime, Physician Superintendent Doctor William Mackinnon established the Morningside Mirror in 1845. As the title suggests, the Mirrorallowed patients to reflect upon their life and thoughts whilst at the REA. Written and printed monthly by the patients of the asylum and running from 1845-1912, this regular source of patient writing provides a lens through which to examine the patient experience of moral treatment.

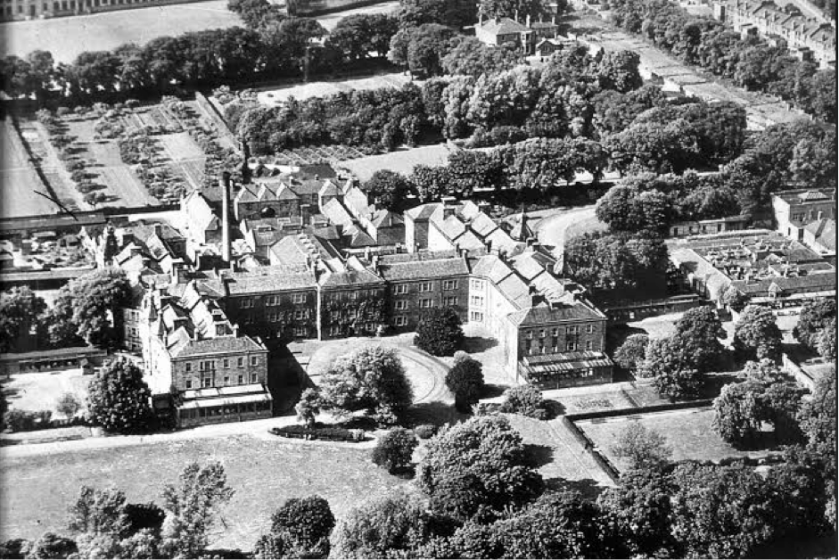

Royal Edinburgh Asylum (1948). Reproduced courtesy of Lothian Health Services Archive, Edinburgh University Library (reference P/PL7/B/M/161).

Amusements and occupation were central tools of the moral treatment regime, which were believed to strengthen the mental faculties and distract patients from morbid thoughts. A diverse range of activities was available at the REA and much of the Mirror was devoted to describing this aspect of daily life. In the summer and autumn, fishing and cricket were central activities and throughout the winter months, the asylum pond became the arena of the REA Curling Club. The ‘weekly ball and concert’ was depicted as the climax of the asylum week. The custom-designed REA ball-room was described as hosting up to three hundred people who consumed currant buns and whisky punch whilst enjoying country dances, singing and dramatic recitations performed by patients, staff and visitors.[6] Occupation was of equal importance to amusements within the moral treatment regime. The magnitude of work done within the asylum is suggested in the Mirror’s accounts of the flourishing asylum economy, which centred upon the asylum farm.

Disclosing the workings of moral treatment to patients was integral to the regime’s system of rewards and punishments. This awareness is evident throughout the Mirror as patients openly disclosed their opinions on the new system. Benevolence and compassion were repeatedly emphasised and patients’ recurrently expressed a sense of amazement at the liberty and leisure they had been granted at the REA for example T.B., who considered his experience of ‘walks and parties of pleasure’ to be ‘a strange contrast to the ancient system.’[7]

The seemingly relentless positivity in patients’ discussions of moral treatment could suggest that the Mirror was little more than a propagandistic mouthpiece for the asylum management. On closer reading of the magazine however, it is clear that a more critical perspective of moral treatment co-existed within the Mirror. Patients occasionally revealed their understanding that the success of moral treatment was selective, only proving fruitful for a portion of the asylum population and several patients openly satirised the illusion of freedom behind which the doors were locked and cold baths awaited, indicating that somatic treatments continued to be widely used in the REA despite the outward appearance of a total faith in moral treatment.

Accounts such as these hint that, by the mid-nineteenth century, confidence in moral treatment was waning and physical methods were increasingly being employed to attain results. Moral treatment was short-lived, enjoying popularity for less than fifty years. Despite this fleeting success, it is evident that the movement from constraint and repression to kind treatment and perceiving the mad as rational beings was a fundamental transition in the history of psychiatry. By analysing sources of patient writing, such as asylum magazines like the Mirror, patient experiences of this key moment can be explored.

[1] Morningside Mirror (MM), 1852, 7, 95, Lothian Health Services Archive, University of Edinburgh (henceforth LHSA), LHB7/13/2.

[2] Jonathan Andrews, ‘The Rise of the Asylum in Britain’, in Deborah Brunton, ed., Medicine Transformed: Health, Disease and Society in Europe 1800-1930 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2004).

[3] Phillipe Pinel, A Treatise on Insanity (Birmingham AL: Classics of Medicine Library, 1983 [1806]), 100.

[4] Ibid., 103.

[5] Ibid., 89.

[6] MM, 1850, 5, 165 & 36, LHSA, LHB7/13/1.

[7] MM, 1847, 2, 46, LHSA, LHB7/13/1.